By TIM REDMOND

DECEMBER 22, 2023

It was a crazy year for housing in San Francisco, with the state forcing to city to adopt new rules for “constraint reduction” to comply with a new construction mandate that nobody, even housing developers, thinks is remotely possible.

The Regional Housing Needs Assessment calls for 82,000 new housing units in San Francisco, 46,000 of them affordable. (I love that terminology; it means the state wants to see 36,000 new units in the city that nobody but the very rich can afford.)

The city has six more years to reach that goal.

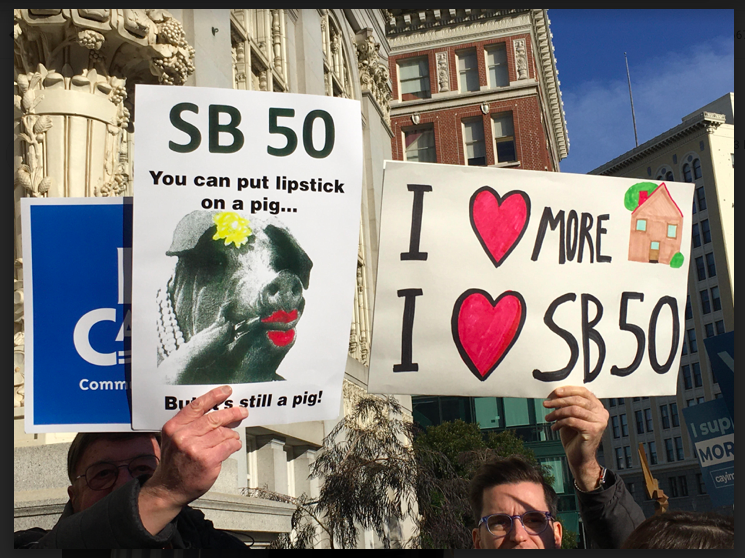

Sen. Scott Wiener’s bills are not going to solve the crisis.

Sen. Scott Wiener’s bills are not going to solve the crisis.

I don’t know anyone who thinks that can happen, even if the city removes all zoning, all environmental review, becomes like Houston and gives developers everything they want.

At the very best, developers like Oz Erikson, who has been building housing in San Francisco for many years, say that we might not see an increase in building permit applications until the end of next year or the year after that.

And the mayor has made it clear that the city will never make the affordable housing goals. And yet, she strongly supported the new state mandates.

The Regional Housing Needs Assessment Goals are supposed to cover the period from 2022 to 2030. It’s about to be 2024. The city has done everything the state wants it to do, some of which is terrible—but only six years are left to do the impossible.

Six years to approve building permits for 36,000 new market-rate units, which means 6,000 a year, and right now, thanks to Capitalism and the federal reserve, there are essentially zero permit applications.

The Terner Center at UC Berkeley, which is historically very Yimby, pro-market-rate housing operation, issued a report this week that discusses the economics of for-profit housing.

It’s a fascinating read, for those of us who like these things, because it explains that even the most modest, mid-sized multi-family housing developments depend on speculative investment capital, which is demanding higher and higher returns:

developers must bring in more equity—private investment with associated expectations for profit to the investor—to cover the gap created by what the bank will not lend.

Those demands for returns are so high that even with all of the policy changes the Yimby folks and the state want, for-profit rental housing doesn’t “pencil out” in most California cities. Meanwhile:

While impactful, these changes may not be politically feasible, and each has their own tradeoffs. For example, reducing impact fees may assist in bringing the projects closer to financial feasibility, but may come at the expense of raising city revenues for critical infrastructure or affordable housing.

In other words, the only way cities can get developers to build expensive housing is to cut the fees that provide the infrastructure to support that housing, meaning that existing residents and businesses will have to pay higher taxes to underwrite the profits of developers.

This is policy insanity. Most modern urbanists have long taken the position, as Tom Radulovich at Livable City has often put it, that “growth should pay for growth.”

So now Sen. Scott Wiener, Gov. Gavin Newsom and the folks at the state Department of Housing and Community Development are going to have to deal with a basic problem:

They are asking cities like San Francisco to approve housing that doesn’t meet community needs and that developers don’t want to build.

The only way interest rates are going to come down in 2024 is if the country goes into a recession, which will convince the Federal Reserve to stop its obsession with inflation—but that will also mean more unemployment and quite possibly fewer people wanting to pay high rents or buy luxury condos.

It takes more than a year just to plan out and look at market prospects for new private housing. So say the “constraints reduction” works like the folks who believe in the magic of the market say it will. Maybe, maybe, there are applications for new market-rate housing in 2024, more likely 2025—but there’s no way we will see what will then be a need for 8,000 units a year.

And the affordable housing goals are going to fail.

What’s the state going to do? Penalize San Francisco for something completely out of the city’s control?

Or admit that this whole RHNA gambit was a fraud?

Tim Redmond has been a political and investigative reporter in San Francisco for more than 30 years. He spent much of that time as executive editor of the Bay Guardian. He is the founder of 48hills.