By Julie Johnson

Updated Jan 25, 2024 7:13 p.m.

https://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/coast-housing-wiener-18624806.php

State Sen. Scott Wiener, D-San Francisco, left, and San Francisco Supervisor Aaron Peskin, right, have dueling views of the need to protect the coastline amid development pressures. Nick Otto/Special to the Chronicle, Lea Suzuki/The Chronicle

Building housing is difficult virtually anywhere in California — but especially along the coast, where there can be an extra layer of permitting.

One of the Legislature’s strongest advocates for more home-building is trying to change that — and he’s starting with the coastline of San Francisco.

State Sen. Scott Wiener, D-San Francisco, introduced legislation this month that would chip away at the authority of the California Coastal Commission, the state agency charged with preserving public beach access and evaluating coastal development, over neighborhood areas along Ocean Beach.

“We’re in a deep housing crisis in California — and that includes the coast,” Wiener said.

The Coastal Commission’s authority over San Francisco is already slim — very few homes actually fall into the coastal zone, which is mostly beach, bluffs and cliffs.

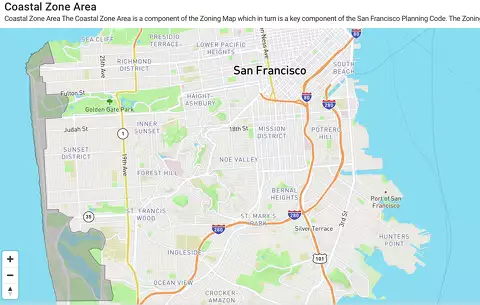

A map shows the jurisdiction of the California Coastal Commission on the western edge of San Francisco. San Francisco government

SB951 would narrow the Coastal Commission’s domain by removing privately owned urban parcels along the city’s western edge from commission oversight. These parcels make up only about 5% of the coastal zone in San Francisco.

The Commission’s 12 members are charged with regulating the use of land in the coastal zone, which typically runs about 1,000 yards inland from California’s shoreline. That means the commission in some cases has final say over coastal developments. The commission has existed since the 1970s, after being created via ballot initiative and enshrined by subsequent legislation called the California Coastal Act.

Mayor London Breed supports Wiener’s legislation, calling it “surgical, smart policy we need to expand housing opportunities.”

Dan Sider, chief of staff for San Francisco planning, said the Coastal Commission’s oversight has not resulted in any changes to development projects in the city’s coastal areas. Sider said that shows the city’s notoriously long permitting process is adequate for vetting projects.

SB951 “gets rid of a bunch of extra bureaucracy that’s not doing anyone any good,” Sider said.

Critics of the bill are less concerned about its impacts on San Francisco than its potential to inspire a slew of other challenges to the state’s authority over development on the coast.

The proposed carve-out represents a small portion of the 840 miles of coastline under the commission’s purview, but SB951 is the first significant challenge to the state agency’s jurisdictional boundaries since the 1980s.

“This has nothing to do with housing,” said San Francisco Supervisor Aaron Peskin, who introduced a city resolution opposing Wiener’s bill this week. “The California Coastal Commission has never been an impediment to housing in the coastal zone in San Francisco.”

Peskin and coastal advocates said they worry SB951 is an opening salvo in a bigger battle over how much to continue protecting California’s coast amid the state’s frantic push for new housing.

“Once you do it in San Francisco they’ll be able to do it in San Diego and Crescent City, and it’s the beginning of the end of the model law that’s worked for California that’s the envy of the nation,” Peskin said.

Susan Jordan, executive director of the California Coastal Protection Network based in Santa Barbara, said Wiener’s policies won’t promote the development of affordable housing and could instead open the door for the type of exclusive, upscale developments curbing public access that the coastal commission was created to prevent.

Jordan said the bill “could signal the unraveling of one of the state’s bedrock environmental laws.”

The Coastal Commission itself hasn’t taken a position on the bill, but commissioners plan to discuss it at their next meeting in February.

“The Coastal Commission understands the acute need for more affordable coastal housing, and is doing everything in its power to support, encourage and facilitate its construction,” said Sarah Christie, the commission’s legislative director. “We approve housing plans and projects from all over the state every month.”

In an interview, Wiener told the Chronicle that cities and counties should have the final authority over housing and business district development decisions — not the Coastal Commission. He said groups opposing new developments have been overly aggressive with appeals and he aimed to “remove a tool that obstructionists will sometimes use to stop new housing.”

Wiener acknowledged that his bill could spur other laws to remove urban areas along the coast from the commission’s zone.

“The most effective way to increase coastal access is to allow people to be able to afford to live by the coast,” Wiener said.

Commission data shows its members intervene infrequently when projects are appealed by members of the public. For example, in 2020, of 604 appeals on projects brought to the commission statewide, only 38 were considered. In 2021, the commission fielded 37 appeals statewide from 1,144 coastal development permits. Of those, the commission found issues in 11 cases and none in the other 26.

In San Francisco, only two projects approved by the city have been appealed to the commission since it was created, according to Coastal Commission spokesperson Christie. The commission considered one, but ultimately made no changes to the project, and rejected the other.

Last year, the Legislature passed a Wiener-authored law, SB423, extending by a decade a previous law streamlining the permitting process for new housing developments across the state (in places behind on state-mandated housing targets). That bill included coastal zones, which had previously been exempt from the streamlining. The Coastal Commission opposed the law, and successfully argued to amend it to exclude areas that are environmentally sensitive or due to face steep impacts from sea levels rising.

In contrast to SB951, the law last year did not remove land from Coastal Commission oversight.

SB951 would also have implications beyond San Francisco. Wiener is proposing to limit the commission’s authority to review some projects in areas where local governments, like San Francisco, have adopted a local coastal program for development, which must be approved by the commission. Currently, the commission can still object to some projects with local coastal programs, and Wiener’s bill would change that.

Laura Walsh, California policy manager for ocean and coastal conservation nonprofit Surfrider Foundation, said local governments use a different set of standards than the commission when approving housing or other developments. The Coastal Commission is an essential ally for coastal preservation, she said.

“What this really comes down to is whether you think the state’s authority over the coast should be weakened,” Walsh said.

Reach Julie Johnson: julie.johnson@sfchronicle.com; Twitter: @juliejohnson

Jan 25, 2024|Updated Jan 25, 2024 7:13 p.m.

Julie Johnson is a reporter with The Chronicle’s climate and environment team. Previously she worked as a staff writer at the Santa Rosa Press Democrat, where she had a leading role on the team awarded the 2018 Pulitzer in breaking news for coverage of 2017 wildfires.

She can be reached at Julie.Johnson@sfchronicle.com.