An economist explains the reality of the housing market, economic inequality, developer profits, threats to the environment—and why the housing mandates don’t ‘pencil out.’

By MICHAEL BARNES

MARCH 12, 2024

Coastal zone residents will soon discover how dysfunctional the latest California Regional Housing Assessment has become.

The RHNA (pronounced REE-na) process, and the housing elements based on it, have always been bureaucratic, expensive, and ineffective. But thanks to the intervention of state Senator Scott Wiener, RHNA has been twisted into a profit-making tool for corporate developers. Across the state, including the coastal zone, cities and counties are being forced to make drastic revisions to their zoning ordinances and other land-use plans.

What Senator Wiener and his allies have managed to accomplish is remarkable. If the state senator had proposed a bill to his fellow legislators that would force many of the state’s cities to rezone for bigger buildings—and then would require cities to rubber-stamp the new building permits—he would not have found the votes. Yet he has managed to accomplish the same thing in a piecemeal fashion.

Wiener’s housing bills, to use a developer term, just don’t ‘pencil out.’

In what follows, I’ll provide my perspective on RHNA and the housing element process, explain how Sacramento has corrupted them, and explore the implications for the coast.

The website of the California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) states:

Since 1969, California has required that all local governments (cities and counties) adequately plan to meet the housing needs of everyone in the community. This process starts with the state determining how much housing at a variety of affordability levels is needed for each region in the state, and then regional governments develop a methodology to allocate that housing need to local governments. California’s local governments then adopt housing plans (called housing elements) as part of their “general plan” (also required by the state) to show how the jurisdiction will meet local housing needs.

California cities are currently in the midst of the sixth RHNA cycle, which for most jurisdictions started in 2021–22 and will end in 2029–30. Here’s how it works:

Step 1: The California Department of Finance provides detailed projections of population and households that span the eight-year RHNA period. These projections are passed along to the Department of Housing and Community Development.

Step 2: HCD starts with the household projections and estimates the number of housing units required to house them. HCD adds housing units to cover older units that will be torn down and to provide enough vacant units to allow housing turnover to take place smoothly. It may make additional adjustments. HCD then allocates the statewide estimates to different regions and passes them along to regional Councils of Government.

Step 3: The regional councils next allocate their allotment to cities and unincorporated areas in their region. For the Bay Area, the council of government is the Association of Bay Area Governments. ABAG allocates household units to all nine counties in the region and 101 municipalities (note that San Francisco is both a city and a county).

Step: 4: In their housing elements, cities and counties then plan for where the additional housing can be built. They must modify zoning if there is insufficient space for new housing.

Creating a housing element is labor-intensive and requires specialized expertise. Many cities hire planning consultants to assist them. I spoke with one highly regarded consultant who confided that their office was limiting housing element work because the “process was broken.” Although the criticism was heartfelt, it is more accurate to say that the process never worked well. This had become obvious by 2003, two decades years ago. The introduction to a 2003 report from the Public Policy Institute of California on the state’s housing element policy stated:

During the 1990s, noncompliant communities were just as likely to expand their housing stock as communities that complied with the law. Furthermore, when other factors were held constant, noncompliance was not a significant predictor of the rate of multifamily development.

In past decades, the housing element process didn’t make much difference. For market-rate (above-moderate income) housing in the fifth RHNA cycle, the majority of cities met their numerical targets, but often not in locations the housing elements emphasized. When it came to subsidized affordable (lower-income) housing, the targets were seldom met because the required subsidies were beyond the means of most cities, and state and federal funding was scarce.

In 2017, things changed. The state Legislature passed a housing bill package of 15 bills (links here and here) and Governor Jerry Brown signed them. Probably the most influential and controversial was Senate Bill 35, authored in 2017 by San Francisco Senator Scott Wiener. The bill streamlined multifamily housing project approvals ministerially (a euphemism for rubber-stamping applications without public hearings) in cities that failed to issue building permits for their share of the RHNA housing allocations. The bill applied throughout the vast majority of the state, carving out only certain environmentally sensitive areas and, notably, California’s coastal zone.

The bill had a serious defect, as the League of California Cities pointed out in its request for a veto to Governor Brown. The league’s letter stated that the bill should:

Require the trigger for ministerial approval of housing projects to be based on the number of entitled and approved applications, a process that a local agency actually controls, rather than building permits, which a developer controls and will not pull until they are ready to construct a project.

Although this may seem like a trivial point, it has major consequences. To understand why, two things need to be explained: First, cities do not build housing. Developers build housing. Cities approve project applications but cannot require developers to build the approved projects. Since approvals typically have a long shelf life of one to three years, developers can bank them and be picky about when they convert them to building permits.

Second, the goal of developers is not to build housing. The goal of developers is to make money. Building housing and making money are not the same thing. Developers are portfolio managers. They hold a range of assets including undeveloped land, project approvals, unfinished projects, market-ready completed projects, cash, and other financial assets.

Developers reallocate their assets to maximize the value of their holdings. Developers are loath to dump so much of their product on the market at one time that they drive their prices down against themselves. Developers are also beholden to their lenders and suppliers. If banks don’t want to lend, or if labor and building materials are too expensive, they may have to put their plans on hold until they “pencil out.” According to this article:

The builders do not care anything about the existing home-sales market, and they don’t care about the housing shortage. They’ll always go slow and steady. …People want an oversupplied market, and we just don’t do that in America.

For all these reasons it makes no sense for SB 35 streamlining to be triggered by developers failing to pull building permits. But in the aftermath of SB 35 becoming law, this is the reality cities face.

Typically a city is not evaluated until the mid-point of the RHNA cycle, when the city reports to HCD the number of building permits issued since the start of the RHNA cycle. At that point, a city is required to have issued at least 50 percent of its share of the RHNA goal for building permits in the region. This determination is made separately for above-moderate (market-rate) housing units and lower-income (combining the low- and very-low-income levels) housing units.

If there is an insufficient number of building permits in either income category, for the rest of the RHNA cycle the city must issue building permits ministerially, or by right, for projects in that income category. The city can only require the developer to meet “objective standards,” those that involve “no personal or subjective judgment by a public official.” If these standards are met, then the building permit is issued without any public meetings or any other review.

It would be almost impossible to write a set of objective standards that would cover every contingency. As an experienced land-use attorney told me, due to a lack of review by planning boards and the public, SB 35 can lead to “unpleasant surprises.” More housing units mean more residents, and more unpredictable demands placed on public resources. The loss of local authority will make planning for utilities, roads, schools, parks, and public safety more difficult.

Cities are often blamed for dragging their feet and creating bottlenecks by issuing approvals too slowly, but the data show otherwise. In their report “New Development in California 2018,” the Construction Industry Research Board stated:

Considering only the projects that are under construction or approved awaiting building permits, there are currently 451,000 new homes and 308 million square feet of non-residential space that will likely be built over the next five years.

Under SB 35, whether cities approve enough housing to meet the RHNA targets makes no difference. And even if developers and trade unions agree they couldn’t possibly build that much new housing, it doesn’t matter. If building permits are not pulled, cities are blamed. The passage of SB 35 left cities vulnerable to schemes that set up cities to fail. All that was needed was a bill that politicized the RHNA process and inflated the numbers. That bill was SB 828.

The Bay Area Council is the leadership organization of the Bay Area’s corporate elites. It lies in the middle of an ecosystem of other pro-development organizations including the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, the Silicon Valley Leadership Group and SPUR. Among legislators in Sacramento, Senator Wiener, who is notorious for his ties to big real estate (see here and here), is their main ally.

The council usually tries to wield its influence from the shadows, but regarding SB 828, the council openly bragged about its success. In the council’s Jan. 29, 2021, Weekly Flash online newsletter, in an article titled (appropriately enough), “Playing the Housing Numbers Game,” The council made this statement:

In the fall of 2017 the Bay Area Council’s housing team met with state Senator Scott Wiener to discuss the ongoing housing crisis, its root causes and what needed to be done to fix things…Out of that meeting came SB 828 (Wiener), a law that makes the calculation process more scientific and accurate. Lo and behold, this year the Bay Area’s RHNA allocation jumped from 188,000 units to 441,000 units.

The Bay Area Council is not interested in making the RHNA calculations more scientific and accurate. The council’s task is to see that its corporate members make more money. Wiener helped them do that by inflating the target number of housing units in the new RHNA process and by changing the wording of the relevant government code to emphasize production.

As with SB 35, the League of California Cities unsuccessfully urged Governor Brown to veto SB 828, and for much the same reason — cities plan and zone for housing, but they do not build housing, and RHNA was created to be a planning tool, not a production tool.

The inflated housing goals in SB 828 set cities up to fail. This was no surprise to Senator Wiener or other senators when they first heard the bill in the Senate Housing and Transportation Committee on May 24, 2018. A speaker from the California Chapter of the American Planning Association expressed this concern, which you can see in the video recording. Go to this link, select the April 24, 2018 hearing, and hit “watch.” At 1:30:00 in the video the presentation on SB 828 starts. The opposition speaker from the planning association starts at 1:43:45 and at 1:45:45 states that SB 828 “sets us up for failure.” The American Planning Association continued to oppose this bill throughout the committee amendment process.

SB 828 empowered HCD to set significantly higher RHNA targets for cities, sometimes more than doubling or tripling the goals from the previous fifth-cycle RHNA. The sixth-cycle target for the state is 2.5 million housing units. That number is almost double that of HCD’s fifth-cycle target of 1.2 million housing units, although the state’s population only grew between two to three percent during the fifth cycle. The City of Berkeley’s goal, for example, has more than tripled, from 2,959 total housing units in the fifth RHNA cycle to 8,934 in the sixth cycle.

To comply with these new targets, in their housing elements cities must first “upzone,” or rezone for higher densities by raising height limits to allow apartment buildings to become taller, and in some cases reducing setbacks from property lines to allow buildings to become wider and deeper. This allows apartments to contain more units.

In an urban residential neighborhood, there might be a height limit of 28 feet, with setbacks of eight feet from the property boundaries. These constraints determine the size of a large imaginary box inside which you are allowed to build a house. In areas that allow apartments, there are much larger boxes of developable space inside which developers can build. The allowable size of this box is a feature of the property, at least until another rezoning, and helps determine the value of the property.

With upzoning, the developable box gets taller (as height limits are relaxed), and sometimes wider and longer (if setbacks are relaxed). The larger developable box makes the property more valuable — without any effort from the property owner. It’s a windfall increase in property values, especially for undeveloped commercial properties. According to land-use economist Cameron Murray, connected landowners capture the benefits of land rezoning:

Land rezoning involves two distinct decisions: the choice to rezone more land for higher-density development, and the choice of the precise area to be rezoned. Political pressure to expand higher value zoning areas is usually argued to come from owners of undeveloped land who may directly benefit, in concert with a wide range of secondary beneficiaries such as banks and construction companies, in a type of ‘growth coalition.’ The secondary decision, where exactly to rezone, involves the allocation of property rights from the community to the owners of the land within the rezoning boundary at the moment of rezoning.

But there’s another bonus for developers. If developers don’t pull enough building permits early in the RHNA cycle, the city and its residents are penalized by being forced to accept streamlined ministerial approval processes. This is true even if cities issue a generous number of approvals early in the RHNA cycle.

Note that this creates perverse incentives for developers to delay construction (perhaps an unintended consequence of SB 828). On the other hand, if cities fail to comply with RHNA rules, there are painful consequences. The combination of SB 35 and SB 828 has led to what cities call “carrots for developers and sticks for cities.”

Part Two: Housing and Community Development’s role

SB 828 went through many versions as it passed through committees in the state Senate and Assembly, but it was never a popular bill. In the concurrence process for the bill, when the senate approved the assembly amendments, SB 828 passed with 22 yes votes, only one more than necessary. According to the rules of the state Legislature, a bill must have a majority of the voting body to pass. Since there are 40 senators, passage requires 21 votes.

Page three of the 8/30/18 Senate Floor Analyses on SB 828 lists these three items that had been refined during the lengthy amendment process:

1) Revises the data COGs must provide to HCD as follows:

- a) Adds, to the existing requirement to provide overcrowding rates, the overcrowding rate for a comparable housing market, as defined.

- b) Adds, to the existing requirement to provide vacancy rates for the existing housing stock and for a healthy housing market, a definition of a healthy housing market vacancy rate as no less than 5%.

- c) Adds a requirement to provide data on the percentage of cost-burdened households and the rate of housing cost burden for a healthy housing market, as specified.

These three requirements were written vaguely enough to leave a wide latitude for their interpretation. HCD implemented these directives in a way to produce absurdly high sixth-cycle RHNA numbers. The lack of transparency was disappointing.

The new requirements of SB 828 were implemented in a way that conflicted with the existing methodology. Before the sixth cycle, the California Department of Finance (DOF) Demographics Unit first projected the state population by county for several years, including the final years of the RHNA cycle. DOF demographers then disaggregated the projected population for each RHNA region into various age cohorts.

Next the demographers applied a housing formation rate (also called the headship rate) to each of the different age cohorts. The housing formation rate is just the percentage of the population in each age cohort that are heads of households. Typically this percentage is low in the younger cohorts, grows for the older cohorts, and begins to decline for the elderly cohorts.

DOF is aware that household formation rates vary over the business cycle. When the economy is strong, children move out of their parents’ houses, and young people tend to have fewer roommates. These changes make the household formation rates grow. When the economy weakens, children move back home, and young people take on more roommates. This makes the household formation rates shrink.

The demographers worried that their household projections would be too low if they were based on current household formation rates. This is due to the continued suppression of household formation caused by the lingering effects of the 2008 Great Recession. So instead of using current rates, they switched to the higher historical formation rates from the decades before the Great Recession. This raised the DOF estimates of the number of households that the RHNA process would need to accommodate.

DOF demographers searched for what economists call a counterfactual model by looking across time for different benchmarks that would allow them to accurately project future household growth. This is a standard professional demographic technique.

HCD’s implementation of SB 828, beginning with the sixth RHNA cycle, introduced a completely different methodology, one that was both incompatible and redundant with the DOF projections. While DOF looked across time for counterfactual benchmarks, HCD looked across space for different benchmarks that explained what household growth should be.

When compared to some other US regions, California has a higher percentage of both overcrowded households and cost-burdened households (households that pay too large a share of their income for rent). HCD attempted to estimate how many more housing units California would need to bring down the rates of overcrowding and cost burden to those of other U.S. regions.

DOF and HCD’s methods both addressed overcrowding, but in different ways. Overcrowding occurs when there are too many people per household. This often happens when low-income families can only afford to share a small housing unit with friends or relatives. In their projections, DOF raised the household formation rate to increase the number of households, which in turn drove down the number of persons per household, decreasing overcrowding. On the other hand, HCD calculated a percentage adjustment rate based on comparisons to other US regions and applied this percentage to increase their number of projected households, which also drove down overcrowding.

Here’s what went wrong: HCD took DOF’s adjusted household projections and applied their simple percentage adjustment to them. But DOF’s projections had already been adjusted upwards. HCD’s final results adjusted the household projections upwards twice. This created a large amount of double-counting and exaggerated the sixth-cycle RHNA estimates of the need for more housing. Critics quickly pointed out this problem and many others, as the next section describes.

The problems with the sixth-cycle numbers were noted by three different organizations:

1) In September 2019, the Southern California Association of Governments (SCAG), the state’s largest Council of Government, filed a formal objection to the sixth-cycle RHNA allocations from HCD. When compared to the fifth cycle, the new sixth-cycle goals more than tripled the number of housing units required in the six-county Southern California region from 412,137 to 1,341,827. The SCAG objections worked within the framework provided by HCD but did a thoughtful, professional job to correct the problems with HCD’s approach. The agency’s response was to ignore the suggestions in a cynical and self-serving letter.

Having seen how little success their Southern California colleagues had achieved, the Association of Bay Area Governments executive board decided not to file an objection to the Bay Area numbers from HCD. Only one member of the ABAG leadership, Novato Mayor Pat Eklund, voted against accepting the figure of 441,176 housing units in the nine-county Bay Area, which more than doubled the fifth-cycle targets.

But there may be another reason for ABAG’s lack of will — it no longer exists as a separate entity. The name ABAG is still used in some planning circles, but it is a polite fiction. ABAG was absorbed in a hostile takeover by the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (here and here). ABAG/MTC, as it is often called, is now a subsidiary of the commission, which itself was formed at the behest of the Bay Area Council, the organization that sponsored SB 828.

2) In September 2020, the private non-profit Embarcadero Institute produced a report, “Double Counting in the Latest Housing Needs Assessment.” This report covered the RHNA allocations to all four major regions in California — Southern California (six counties), the Bay Area (nine counties), the Sacramento region (six counties), and San Diego County. Along with the formal complaint by the Southern California Association of Governments, the report uncovered problems with HCD’s analysis of overcrowding and cost burden.

3) In September 2021, state Senator Steven Glazer requested an emergency audit of the RHNA process. In response to Glazer’s request, in March 2022 Michael S. Tilden, the Acting California State Auditor, issued a blistering critique of RHNA:

Overall, our audit determined that HCD does not ensure that its needs assessments are accurate and adequately supported. …This insufficient oversight and lack of support for its considerations risks eroding public confidence that HCD is informing local governments of the appropriate amount of housing they will need.

Although HCD claimed to have addressed the report’s concerns, it provided few details. Unfortunately, the state auditor has no enforcement authority. Since HCD is a sub-agency of the cabinet-level California Business, Consumer Services and Housing Agency, it would be up to Governor Newsom’s office to insist that HCD act more consistently. So far, the Governor has shown little interest in doing so.

Back in the fall of 2017, when Wiener planned with the Bay Area Council to inflate the RHNA targets, it appears they were a little too successful. As discussed in detail in Part Three below, it is physically impossible to achieve the overall RHNA targets. It is financially impossible to achieve affordable housing targets. Even the market-rate (above-moderate) targets will be extremely difficult. Developers will not oversupply and flood the state with market-rate housing to the point they drive down their profits.

Part of the problem may be that Wiener and his staff did not meet with the Department of Finance demographers to understand their methodology, which underpinned the household forecasts used in the RHNA process. This would explain the double counting detected by the Embarcadero Institute. I had an opportunity to ask Senator Wiener about this, and his non-response left me with the impression that his staff did not meet with the demographers or understand their methodology. But judge for yourselves. Here is a video interview with Senator Wiener. My question begins at 57:25.

However the goals were reached, the post-SB 828 RHNA targets are exaggerated to the point of absurdity. Cities and counties are being set up to fail. Yet along with HCD, hundreds of cities and counties across the state will spend more than a billion dollars in staff time and consultant fees to pursue a housing element fantasy.

Part Three: HCD’s 2022 statewide housing plan

In March 2022 HCD published the 2022 Statewide Housing Plan (online here, download here). The Housing Plan brought together the RHNA housing goals for all 539 jurisdictions in California — 482 cities and 58 counties (San Francisco is both a county and a city). Between the fifth (2014–2022) and sixth RHNA cycles (2022–2030), the population of California grew by just a few percentage points, while the RHNA targets more than doubled. This is due to the redundant ad hoc adjustments required by SB 828.

In the above graph, taken from the 2022 Statewide Housing Plan, note the two lower blocks of the column on the right. Those blocks represent the target amounts of housing for very low- and low-income households. The sixth-cycle RHNA goal for these households is slightly more than 1 million housing units. At a subsidy cost of $750,000 per housing unit, the RHNA targets would require $750 billion in subsidies.

Inclusionary zoning could lower the cost per unit, while building in the coastal zone could raise the cost to $1 million per housing unit (this was confirmed by Terner Center Policy Director David Garcia at the December 2023 California Coastal Commission meeting in Santa Cruz, available online here, starting at 42:30).

The main source of funding for deed-restricted affordable housing is the Federal Low Income Housing Tax Credit Program (LIHTC). This program allocates to the states “the equivalent of approximately $9 billion in annual budget authority to issue tax credits.” Even if California could spend the whole annual federal allocation for eight years in a row, that would amount to $72 billion, or about one-tenth of the amount needed to meet the RHNA affordable housing target. Other sources are available (see here and p. 7 here), but even under the most optimistic assumptions, the RHNA affordable housing targets are wildly unrealistic.

The sixth-cycle RHNA goals also call for 2.5 million housing units to be constructed in eight years, more than 300,000 housing units annually. The graph above shows the annual number of housing units permitted in California since 1980. The horizontal line near the top of the graph (Units Needed) indicates the annual number of housing units required to meet the sixth-cycle RHNA target of 2.5 million units (312,500 units annually). In only one year since 1980, in 1986, did the state produce more than 300,000 housing units. An earlier HCD report (here, p.6) extends this data back to 1954. That report shows that in only two years out of the last 70 did the state produce more than 300,000 housing units — in 1963 and in 1986.

After the Great Recession of 2008, which hit California particularly hard, the state’s housing market collapsed, and along with it the residential building industry and its workforce. California now produces slightly more than 100,000 housing units annually. It is not possible to quickly triple production and hold it at that level for eight years. Building more than 300,000 housing units annually for eight years has never occurred in California, and it’s extremely unlikely it could be achieved in the sixth RHNA cycle. Post-Covid, the national construction industry labor shortage has been severe.

The constraints on housing production in California have also been noted by William Fulton, the publisher of California Planning and Development Review. In a January 7, 2024, article, “Does California have Limited Housing Development Capacity?” Fulton states:

After the Great Recession, the overall capacity of the planning and development system shrunk significantly and, apparently, permanently. There are fewer developers, financiers, and planners in California than there were 15 years ago. …The overall planning workforce in the public sector — somewhat dependent on the fees generated by development applications — permanently declined. It’s entirely possible that the development system is producing as much housing as it’s possible to produce with the capacity it has.

The Governor’s Office, HCD and the Legislature all seem to see California’s housing production system as a black box model with a linear response — to double the output, just double the inputs. Thus if HCD tells all 539 cities and counties in the state to plan for twice as many housing units, the result magically will be, eight years later, twice as many apartments, condos and single-family houses. But sadly, the world doesn’t work this way.

Housing development is a monopolized industry, like many others in the United States. Monopolists face downward-sloping demand curves. They do not keep building to the point where they drive down prices against themselves. It is the developers who constrict supply as demand changes. Constricted supply is baked into monopoly capitalism.

A review of the fifth-cycle RHNA results makes this more clear. Although the fifth-cycle targets were about half the size of the sixth cycle’s, out of a total of 539 jurisdictions, 251 (46.6 percent) failed to meet both the above-moderate and lower-income targets. Another 246 jurisdictions (45.6 percent) met their above-moderate income targets but failed to meet their lower-income targets. Only 42 jurisdictions (7.8 percent) met both the lower-income and above-moderate income targets.

When developers fail to produce enough housing to meet HCD’s inflated sixth-cycle targets, it will not be the fault of local jurisdictions. After approximately 150 housing bills since 2017, most local control has been eliminated by the state Legislature. Thus it will be less and less credible for legislators to continue to blame cities as new housing units fail to arrive. This fiasco will come to an ugly conclusion when HCD’s sixth-cycle targets are met almost nowhere in the state. Then it will become clear that Sacramento never had a coherent plan to build housing.

Part Four: New developments for the Coastal Zone

William Fulton, in the California Policy and Development Review, notes:

SB 35 requires ministerial approval for certain projects containing affordable housing in cities that are not meeting their housing targets under the Regional Housing Needs Assessment, which these days is practically all cities. …This year, as has been widely publicized, SB 35 was extended and expanded by SB 423, which passed after a brutal battle over whether it should be applied in the coastal zone – a battle Wiener won.

SB 35 has a sunset date in 2026, so Senator Wiener got an early start in replacing his original bill with a new version, SB 423. Compared to its predecessor, SB 423 had more lenient labor standards and further restricted the review of developers’ building applications for conformance with objective standards. Under the new bill, the review must be handled at the staff level—no oversight by planning commissions or city councils will be allowed. As proposed, SB 423 had no sunset date, and unlike its predecessor SB 35, the new bill would apply to the coastal zone.

As the bill worked its way through the committee process, first in the Senate and then in the Assembly, a sunset date of 2036 was added, the labor rules were tweaked, and then on July 10, 2023, the bill landed in the Assembly Natural Resources Committee, chaired by Assembly-member Luz Rivas. The committee hearing was unusually contentious. The relevant portion of the meeting can be viewed here, starting at 1:12:00.

Chair Rivas was opposed to allowing the bill out of her committee unless its streamlining provisions would not apply in the coastal zone, as had been the case in SB 35. Her stance was supported by three committee members, all from coastal districts: Dawn Addis (AD 30, Morro Bay), Al Muratsuchi (AD 66, Torrance) and Gail Pellerin (AD 28, Santa Cruz). Their comments begin at 2:19:00.

Earlier in the legislative session Rivas and her allies on the Natural Resources Committee had been able to modify AB 1287, a bill carried by Assemblymember David Alvarez (AD 80, San Diego) that would have exempted density bonus projects from the Coastal Act. In committee, Rivas and a majority of the committee members were able to restore the Coastal Act Savings Clause, which states that density bonus law shall not be “construed to supersede or in any way alter or lessen the effect or application of the California Coastal Act of 1976.” This assured that the bill’s enhanced density bonus benefits would continue to be harmonized with a jurisdiction’s local coastal plan.

However, the committee was not as successful with SB 423, and the version of the bill that passed largely superseded the Coastal Act. Seven committee members voted in favor of SB 423, while four effectively voted no with abstentions. Assemblymember Rivas was later removed as chair of the Natural Resources Committee.

SB 423 opens a Pandora’s Box. For the first time since the creation of the California Coastal Act 50 years ago, a whole class of development, multifamily projects, will be exempt from our state’s landmark coastal management legislation. In the long run, the particulars of the bill may not matter. Wiener and his allies have created a precedent and will continue to build upon it to disregard the will of the voters expressed in the 1972 initiative that led to the creation of the Coastal Act.

SB 423 is, at its core, a device for extending the carefully manipulated RHNA process into the coastal zone. RHNA is a ticking time bomb. Four years into the eight-year cycle of each region, if developers haven’t pulled permits for at least half of the jurisdiction’s RHNA allocation, the approval process becomes ministerial. This deregulation by default effectively nullifies the application of the Coastal Act. In addition, the interaction of ministerial approvals and the concessions required by density bonus law will prevent cities from enforcing even their limited objective standards.

Given the absurdity of the RHNA goals, ministerial approvals will go into effect in almost all California cities and counties. The table below shows the dates when the RHNA ministerial approval processes will begin in all 15 counties in the coastal zone.

Final thoughts

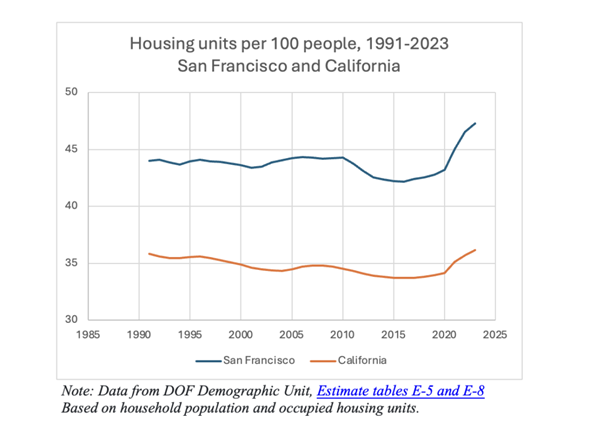

The May 15, 2023, edition of CalMatters featured an article titled, “California is losing population and building new houses. When will home prices come down?” In the article, reporter Ben Christopher noted, “There are now more homes per person — 3,770 units for every 10,000 Californians — than there have been since at least 1991.

The graph above confirms the CalMatters reporting. Three things stand out in the graph. First, the number of housing units per capita is now higher than it has been since at least 1991, for both San Francisco and California (this also true for Los Angeles and San Diego). Second, housing units per capita are much lower for the whole state than in San Francisco. Like many large, dense cities, San Francisco tends to have smaller households due to the lack of families with children, and the large number of young people who either live alone or with a few housemates. Third, the boom-and-bust tech cycle, along with remote work, has reduced San Francisco’s population proportionally more than the rest of the state, raising the amount of housing available for those who remain.

Sacramento has been telling California residents that we are in the midst of a “housing crisis.” Yet, on average, overcrowding has been reduced in California since 1991. The real problem is not the amount of housing, but the mismatch between income and rents. We are in an affordability crisis due to growing income and wealth inequality.

This is not just a problem for California. According to census definitions, about 50 percent of US renters are considered housing cost-burdened because they pay more than 30 percent of their income for housing. In California, about 55 percent of renters are housing cost-burdened — higher than the U.S. average, but not by much. Housing costs are a national and even an international problem.

California’s housing affordability crisis will not be solved by building more market-rate housing in the coastal zone. Like the rest of the state, lower-income households in the coastal zone need affordable housing, at least in regions where the zone extends more than a few hundred yards inland. But the constraint is not lack of land zoned for apartments and condos, it is lack of subsidies and meaningful inclusionary mandates.

Senate Bill 423 will be just the first of many bills that seek to undermine the integrity of the Coastal Act and destroy its ability to preserve the coastal zone. The result will be a Tragedy of the Commons. The Coastal Act has preserved the California coast for the common benefit of all our state’s residents. Unfettered coastal development will destroy the natural beauty of California’s coast. Wiener may argue that his bills are only modest adjustments of the commission’s authority, but as we have seen with state housing policy, the cumulative impact of dozens of bills will not be modest.

Because the Coastal Commission has conserved the coast as well-managed commons, real estate developers can maximize their profits by constructing luxury residential projects in coastal communities. Many of these will become short-term vacation rentals or private vacation homes that are unoccupied much of the year. In the coastal zone increased supply will never bring down housing prices. Housing prices will always be skewed by the endless interest of global investors in California’s coastal real estate.

Let me close by repeating to the words I wrote to the State Auditor regarding RHNA:

Your work is critical because the sixth-cycle RHNA is a fraud. I do not know, and perhaps none of us will ever know, how much this is due to malfeasance, and how much to incompetence and miscommunication. But perhaps that doesn’t matter. Regardless of how the problem was caused, the goal should be to prevent the damage that will spring from it.

The Coastal Commission should not overestimate the amount of support and goodwill it has in Sacramento. Many elected officials there would gladly hand over the coastal zone to the real estate industry. After all, the industry is a major source of their campaign funding. Decades of environmental progress could be undone in less than a generation.

It has been more than 50 years since the voters approved the formation of the Coastal Commission in 1972. They created the commission in part because they didn’t trust local leaders and Sacramento politicians to manage the coastal zone wisely. The ability to enjoy our state’s coastline is the right of every resident. Californians saved the coast in 1972, and now, half a century later, we need to rally to preserve the Coastal Act.

Michael Barnes earned a B.A. and M.A. in economics in the 1980s and worked as a budget and economic analyst for the State of Washington in Olympia, WA. He pursued an economics Ph.D. at UC Berkeley before switching careers and joining the UC staff. He retired in 2017 after spending the final 11 years of his career as the science editor for the UC Berkeley College of Chemistry. He served on the Albany City Council from 2012-2020. Between attempting to learn to surf several years ago and more recent and successful cycling tours, he has visited almost every county in California. Email: michael7barnes@gmail.com

48 Hills welcomes comments in the form of letters to the editor, which you can submit here. We also invite you to join the conversation on our Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

This says it all: “Senate Bill 423 will be just the first of many bills that seek to undermine the integrity of the Coastal Act and destroy its ability to preserve the coastal zone. The result will be a Tragedy of the Commons. The Coastal Act has preserved the California coast for the common benefit of all our state’s residents. Unfettered coastal development will destroy the natural beauty of California’s coast. Wiener.”

“It has been more than 50 years since the voters approved the formation of the Coastal Commission in 1972. They created the commission in part because they didn’t trust local leaders and Sacramento politicians to manage the coastal zone wisely. The ability to enjoy our state’s coastline is the right of every resident. Californians saved the coast in 1972, and now, half a century later, we need to rally to preserve the Coastal Act.”

Regaining control of Sacramento policy making, and the abolishmemt of failed and troubling housing laws will be key to saving California and our coastline, the environment.